MAGNA GRAECIA

Two set-piece frescos dominate.

In one, the god Apollo is seen trying to seduce the priestess Cassandra. Her rejection of him, according to legend, resulted in her prophecies being ignored.

The tragic consequence is told in the second painting, in which Prince Paris meets the beautiful Helen – a union Cassandra knows will doom them all in the resulting Trojan War.

The Greek dialects in Magna Graecia—the collection of Greek colonies established in southern Italy and Sicily—were indeed diverse and unique. These colonies, founded between the 8th and 5th centuries BCE, became thriving centers of Greek culture and influence, yet the dialects spoken in these areas evolved in distinct ways from the Attic dialect spoken in Athens and other parts of Greece.

Some of the most prominent dialects in Magna Graecia included:

Doric: The Doric dialect was perhaps the most widespread in Magna Graecia, especially in the cities of Syracuse, Catania, and Rhegium. Doric was also spoken in the colonies along the western coast of Italy (e.g., Tarentum), as well as in Sicily. This dialect was known for its conservative features and was used in many monumental inscriptions and poetry.

Chalcidian: This dialect was spoken in colonies founded by the Chalcidians (from the island of Euboea) and was particularly prevalent in places like Naxos and Catania. It was a variant of the Ionic dialect, which had its roots in the eastern Greek world, and it exhibited some unique characteristics influenced by the local conditions.

Ionic: In areas such as Cumae and some parts of the Campania region, Ionic Greek was spoken. This dialect was associated with the more eastern Greek world and was more flexible and adaptable than Doric in its linguistic features.

Aeolic: In the northern part of Magna Graecia, particularly in the colony of Thurii, elements of the Aeolic dialect were present. This dialect was used primarily in Lesbos and Boetia but made its way into some of the colonies of southern Italy.

The Greek colonies in Magna Graecia were not only influenced by the language of their Greek founders but also incorporated local elements from the Italic and Sicilian languages, which led to further linguistic variations. Over time, these dialects developed their own unique features, contributing to the cultural richness of the region.

These dialects were not just spoken languages—they were also reflected in the literature, poetry, and inscriptions of the region. Poets like Pythagoras, the playwright Euripides (who was connected to the colony of Syracuse), and philosophers from these colonies utilized these dialects in their works, adding to the lasting cultural legacy of Magna Graecia.

Ultimately, the Greek dialects of Magna Graecia represent an important chapter in the history of the Greek language, marking the spread of Greek culture far beyond its homeland, and revealing the adaptability and diversity of Greek civilization.

MAGNA GRAECIA /ribbed NESTORIS, a GREEK CEREMONIAL VESSEL, with a use analogous to that of the AMPHORA, from APULIA in SOUTHERN ITALY, of the Gnathia technique. 300 BC GETTY Museum Collection. No. 78.AE.320.

Beginning in the 5th century BC, pottery flourished in Southern Italy. APULIA, a region characterized by its incredible artistic richness and dynamism, became an important center of production. During the fourth century, Apulian potters created pottery in a new style known as GNATHIA ware, named after the eastern Apulian town of Egnazia, where the first examples of this technique were first discovered in the 19th century, which appeared around 370/360 BC.

Gnathia vessels were traded throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and quickly gained influence throughout the region. Although they may have originated there, they were soon manufactured in many centers in southern Italy and SICILY. The technique was based on the application of additional color, mainly white, yellow and red, to enliven the surface of a black-glazed vessel. The black varnish is often decorated with painted floral motifs in red, white or yellow. Later, after 330 BC the white color dominated more.

Decorative subjects that once included love affairs, scenes from women’s lives, theatrical scenes and Dionysian motifs are now limited to tendrils of vine, ivy or laurel fruits, theatrical masks and, small human heads hares, doves and swans. While the lower half of the vessels was now often decorated with ridges.

The production and quality of Greek colonist potters working in Southern Italy increased greatly after the Peloponnesian War, when Attica’s exports fell sharply, and it was probably concentrated around Taranto, with workshops in Egnatia, Canossa and Sicily. The Greek craftsmanship of the settlers of Lower Italy in the 4th century BC. created a fusion of the Ionic (Attic) styles and the corresponding Doric (western Greek colonies), combining them with a remarkable native Italian aesthetic. The five dominant regional schools of pottery in Southern Italy were: Apulia, Sicily, Lucania or Laucania, Campania and Poseidonia (Paestum).

In the photo, the vase, which I mentioned at the beginning, with the characteristic shape produced in Southern Italy, called nestoris. From Apulia, of the Gnathia technique, 300 BC. With dimensions: 50.9 × 26.3 cm (including handles). The type of this nestorid is A, (according to the evolution of the shape of the body and the handles, there are 3 types). Neckless with flared lip and two horizontal and two upright high handles. The upright grips are decorated with tablets, here decorated by eight-pointed stars, surrounded by a dotted circle in additional white. On the shoulder there is a decoration of ivy tendrils with leaves and fruits rendered with white dots. The larger part of the lower part, about 3/4, is decorated with vertical ridges.

Akragas. Anfora attica a figure nere del Pittore Taleides: Teseo uccide il Minotauro; intorno si trovano due coppie, con uomini nudi e armati di lancia e donne interamente vestite. Scoperto ad Agrigento e infine pervenuto al MET Museum di New York, il vaso presenta la firma di Taleides e la scritta “Klitarchos kalos” (Klitarchos bello). 540-530 a.C.

MAGNA GRAECIA 320-280. before the era of PUGLIA

Golden fibula Gold, length: 8,8 cm,

Boston Museum of Fine Arts

By: Олег Марголін: A RARE GREEK GOLD TWELFTH STATER OF TARENTUM**OR TARANTO = ΤΑΡΑΣ (GENETIVUS FORM: ΤΑΡΑΝΤΟΣ)

(CALABRIA). FROM THE TIMES OF ALEXANDER THE MOLOSSIAN 333 BC. AV TWELFTH STATER – HEMILITRA (6.5mm, 0.43 g, 7h). RADIATE HEAD OF HELIOS FACING SLIGHTLY RIGHT/ THUNDERBOLT; TARAN ABOVE,AΠOΛ BELOW . Fischer-Bossert G3b (V3/R3) = Vlasto 14 (this coin); HN Italy 906; SNG ANS 977; SNG BN 1775-6; SNG

**THE ORIGIN OF THE CITY OF TARANTO DATES FROM THE 8th CENTURY BC, WHEN IT WAS FOUNDED, AS a GREEK COLONY, KNOWN AS TARAS . TARAS GRADUALLY INCREASED ITS INFLUENCE, BECOMING A COMMERCIAL POWER AND A CITY-STATE OF MAGNA GRAECIA AND RULING OVER MANY OF THE GREEK COLONIES FOUNDED BY SPARTA IN THE 8th CENTURY BCE, AS PART OF THE EVEN OF THE OTHER GREEK

COLONIES, AS THE CORINTHIAN ONES (SYRACUSE, ETC….)

Copenhagen 833; SNG Lloyd 188; Jameson 145; McClean 596 (all from the same dies). Good VF, underlying luster, slight die wear on reverse. VERY RARE.

And when everything calms down, a one-day excursion to one of the most shocking places in the ancient Greek world is a must. Until the 1990s, Ancient Messina, the city founded by the general Epaminondas in 369 BC and which was the cradle of Messinia, was nothing more than an archaeological site with few remains. The vision of archaeologist Petros Themelis, unprecedented for Greek standards, led to its systematic discovery and restoration. Today, in tourist terms, it is considered the rival of Ephesus and proves that such visions can resurrect the enormous cultural wealth of the country, its greatest strength, which in many cases is woefully neglected.

The four-column propylon of the gymnasium of Ancient Messina after the restorations

The impressively rare funerary monument of Ancient Messina

The funerary monument K3, as it was conventionally called, belongs to a series of funerary monuments and Heroes of various forms that were built around the Gymnasium and Stadium of Ancient Messina and belonged to heroes and prominent families of the Messinian elite. But why did the members of these families enjoy such heroic honors after death from their fellow citizens and had the privilege of building their funerary monuments within the walls, and even next to public spaces such as the Gymnasium? According to archaeologist Petros Themelis, the purpose was not to demonstrate the wealth and luxury of the Messinian aristocracy, but the constant contact with the world of dead ancestors cultivated in the young the right role models for their future lives. The Gymnasium and the Stadium were not only places of physical exercise but also places of spiritual training for a three-year term of adolescents with the aim of their initiation and integration into society as worthy warriors, athletes and citizens. They were also centers of the city’s public life.

It was built at the beginning of the 3rd century BC and in its chamber eight cist tombs of an aristocratic family were found with the names of its members engraved on the Ionic epistle of the monument. The conical roof, reminiscent of a tent, rests on a square chamber and is crowned with a Corinthian capital on which a solid stone vessel (hydria or amphora) dominates, a combination unique for the data of ancient Greek architecture. Its restoration was completed in 2018 as part of the systematic restoration and promotion of Ancient Messina by Petros Themelis.

MAGNA GRAECIA/Campi FLEGREI.

According to the poet VIRGIL, this might be your land, here you might find your history.

Known as the “Burning fields”, this large area to the north of NAPLES, is one of the MOST fascinating land in the CAMPANIA region. The PHLEGREAN FIELDS (from the Greek FLEGRAIOS, or “BURNING”) is an enormous volcanic area that extends to the west of the Gulf of NAPLES from the hill of POSILLIPO to CUMA, and includes the islands of NISIDA, PROCIDA, VIVARA and ISCHIA. The ancient town of Cuma was situated close to the current city of Naples, and traces of the earlier city can still be seen nearby. The setlement was founded by the ancient Greeks in a location that had been occupied since prehistoric times, and is notable as being the first Greek settlement in Italy.

The families and descendants from the original settlement at Cuma went on to create further towns and villages, including the one that was later to become Naples.

For years people talked about the opportunity to visit an “Underground Naples,” with evidence of Naples in its first period when it was founded by people from Cuma – in fact, there is an “Underground Naples”, which today can be visited by tourists interested in antiquities. The brief historical notes below may be useful to those who would like to explore Naples as it was “in the time of Cuma”.

Temple of Serapis in Pozzuoli, on whose columns the marks left by marine organisms (lithodomas) are visible during the phases of subsidence of this sector of the Campi Flegrei caldera and therefore submersion under the lm, which occurred due to bradyseism.

Cuma: early origins

During the mid-seventh century BC the Coumans built the Greek city of Parthenope between the hill of “Pizzofalcone” and the “Megaride” island, once connected to the mainland and now the seat of the “Castello dell’Ovo”, on a promontory overlooking the sea, where there was the port. The settlement of Parthenope, as we can see from ceramic materials found in a necropolis of the city, seems to have been a lively place from the first half of the 7th century to the second half of the 6th century BC.

At the end of the sixth century BC the Coumans founded “NEAPOLIS ( = ΝΕΑΠΟΛΙΣ”= NEW CITY)on a plain sloping from north to south towards the sea. The place where the “first” NAPOLI was located is now included in the heart of the Old Town of Naples. The walls were arranged around the perimeter of the plain, and cemeteries surrounded the city on three sides. The oldest part of the city walls dates back to the early 5th century BC.

The walls were reinforced at the end of the 4th and at the end of the 3rd century BC, with further additions in the early Middle Ages. The acropolis of the Greek city shows the agora, the forum, the Odeon and the “macellum” with business functions, while the shrines were located in the higher part of the hill, with the Temple of Castor and Pollux.

The best preserved structures date back to the Flavian age, and, in any case to the imperial age, with references to outstanding figures of emperors such as Augustus and Nero.

In fact, thanks to archaeological excavations a Marblehead dating from the middle of the first century came to light, which, according to some scholars, represents the Emperor Nero. From the historical point of view, this is proof that the excavation area was once a place of imperial cult.

Not far away there are the remains of the theatre where the Emperor Nero performed in front of audiences from Naples with poetry readings and musical exercises. In fact, the Emperor Nero was in Naples in 64 AD to preside over the so called “isolympic” games [equal to Olympic Games] remaining then in Benevento to attend the Gladiatorial games. Naples was also a favourite city of the Emperor Augustus.

By the will of Augustus, the cult of the emperor was banned in Italy. The only exception was Naples, which was a “Roman city” in the first century BC, but remained a “Greek city” for all practical purposes. In the city a series of Olympics games, like athletics, heavy athletics, horse racing, art, poetry, theatre and music took place.

After Augustus, Naples remained a reference point for the emperors and the Roman ruling classess, who built villas of extraordinary beauty, and, of course, with “sea views.”

In order to safeguard the delicate environmental EQUILIBRIUM, the area was made into the PHLEGREAN FIELDS Regional Park in 1997.

CUMA with its magnificent ACROPOLIS perched on a high crag by the sea was founded by the CHALCIS of EUBOEA (Greek islands of EUBOEA and SKYROS) around 730 B.C., who were ALREADY established at PITHECUSAE (modern ISCHIA Island).

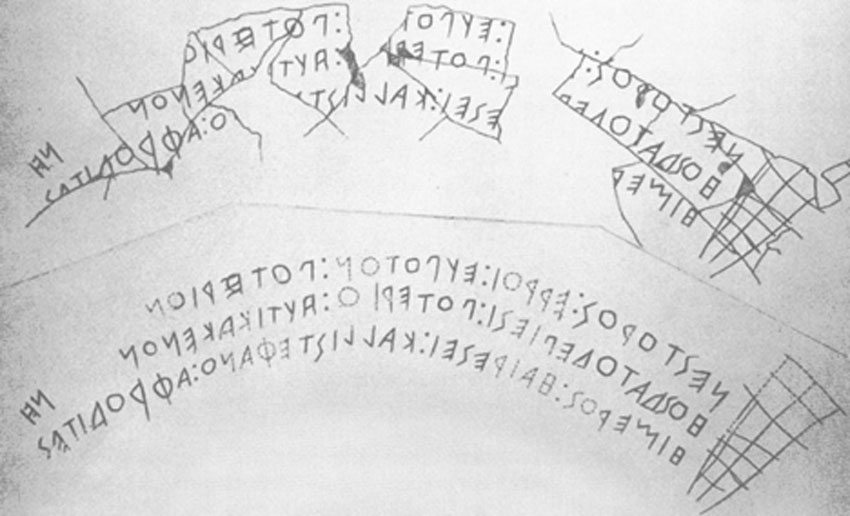

PITHECUSAE: Nestor’s Cup is an eighth century BC wine cup discovered in 1954 in the San Montano cemetery associated with the ancient trading site of Pithekoussai in Magna Graecia, on Ischia, an island in the Gulf of Naples (Italy). The cup has a three-line inscription, one of the earliest surviving examples of writing in the Greek alphabet. It is currently held by the Museo Archeologico di Pithecusae on Ischia. The cup was originally made in the eastern Aegean, either on the island of Rhodes or in northern Ionia. The inscription was scratched into it after its manufacture, possibly during a communal drinking event known as a symposium. It was found by Georgio Buchner in 1954 in a cremation grave dating to the end of the eighth century, which contained the remains of three adults as well as burnt animal bones, a fibula and fragments of other vessels. The cup is a SKYPHOS or kotyle[a] decorated in the GEOMETRIC style, 10.3 cm (4.1 in) in height and with a diameter of 15.1 cm (5.9 in). It was made around or before approximately 735–720 BC, either on the island of RHODES or in northern IONIA. It was found in 1954[ in a cremation grave dating to approximately 720–710 BC[ on the island of ISCHIA, home of the EUBOEAN Greek EMPORION (=trading-site) of PITHEKOUSA.

The cup’s decoration has been called “typical, conventional, and predictable” by Nathan Arrington. It consists of two panels, the uppermost of which is divided into four metopes decorated with diamonds, a stylised drawing of a sacred tree and meander hooks,[ a device common on Attic skyphoi of the Geometric period.The lower panel includes a zigzag decoration, but also blank spaces, one of which was used for the inscription.

Neapolis, Parthenope and Naples in the time of Cuma

When we say that Naples was a colony of Cumae, that is correct – but the history of the origins of Naples has long been controversial, since Naples was known by two names, “Parthenope” and “Neapolis.” The issue of the “names of Naples” dates from antiquity.

Strabo [58 BC-25 AD], in the fifth book of his “Γεωγραφικά” [Geography], wrote that the colony founded by the Coumans was called “Neapolis” [= New City]. However, some ancient historians like Pliny the Elder [23-79 AD] said that Naples was also called Parthenope, because the sepulchre of the siren “Parthenope” was here. For Pliny, Parthenope and Naples were the same city.

However, Lutatius Catulus [consul in 102 BC] wrote that Parthenope was located in a different area than Naples, and that Parthenope was older than Naples:

Lutatius wrote in the fourth book that some Cumaean colonists were moved away by their parents and they founded the city of Parthenope, so named because of the sepulchre of the siren Parthenope. Later on (the new city), thrived for fertility and beauty of the landscape, and attracted more immigration, and Cuma, for fear of depopulation, decided to destroy Parthenope. After that, however, the Cumans were struck by a plague and, on the instructions of the oracle, restored the city and also the worship of Partenope. Because of its recent foundation, the city was called ‘Neapolis’ that is ‘the New City’”

The most recent archaeological excavations have shown that, in reality, the Cumans first founded Parthenope and then later founded “Neapolis”.

See also the history of Cuma to learn more about the ancient origins of the town.The first indigenous settlements of Cuma are on the acropolis and date back to the end of the ninth-first half of the eighth century B.C. The city was the oldest Greek colony in the West, founded by groups from the cities of Chalcis and Eretria, who at the same time had also settled in the island of Ischia

The temple shows remains of almost all the complex phases of life of the building: the foundations of the late seventh century B.C., the large foundation blocks of the Samnite age, the brick pillars of the early imperial age, the early Christian baptistery; finally, the medieval tombs that occupied the five naves of the basilica of San Massimo, protector of Cuma, abandoned in 1207, when the city was cleared after the attack of the Neapolitans.

The first indigenous settlements of Cuma are on the acropolis and date back to the end of the ninth-first half of the eighth century B.C. The city was the oldest Greek colony in the West, founded by groups from the cities of Chalcis and Eretria, who at the same time had also settled in the island of Ischia (Pithekoussai the Greek name): as shown by the first Greek tombs, the colonization must have taken place in the second half of the eighth century B.C., in accordance with the traditional foundation date handed down from ancient literary sources (730 B.C.). Since the beginning the plain was occupied where later, from the IV sec. a.c., the lower city would have risen, overlooking the lake of Licola. The cliff of the acropolis dominates the plain, allowing the control of a vast stretch of coast, from Miseno to Circeo.

Cuma, panorama from the acropolis

Naxos of Sicily. Terracotta counterface with fragmentary Silenian mask. The original pigmentation is still partially retained, including the redness of the ears and the lines of the thick beard. From the settlement of the 5th century BC. Locally manufactured. Naxos Archaeological Park Antiquary (Naxos Gardens, ME)References

Among the epithets of Athena there is also that of PANDòROS (giver of all things), connected to the story of Pandora, the first woman. The idea of creating this creature came to Zeus, who charged Hephaestus, master of all those who work metals, to create a clay statue that reproduced in every way the appearance of a real woman. All the divinities were called to give gifts to that splendid creature; Athena taught her embroidery, weaving and all the other practical virtues that a woman should be endowed with. She also dressed her in beautiful clothes and precious necklaces and placed a garland of flowers on her head. Hermes and Aphrodite also contributed to making the creature graceful and Zeus, blowing on the skillfully shaped clay, gave her life. She was called Pandora, “she who has all the gifts”. Then before sending her to earth, Zeus gave her a vase and ordered her never to open it.

Once she arrived on earth, imagining who knows what treasures her vase contained, after having married Epimetheus, no longer able to resist her curiosity, she opened the vase: from it in a sinister hiss came out Lies, Suspicion, Hunger, Jealousy, Hardship and every other misfortune. Pandora immediately closed the vase, but by then all the evils that would afflict humanity from that moment on had come out; at the bottom of the vase there was only one last gift: Hope (Elpìs).

It seems that Athena was also related to rivers, as in the Peloponnese as in Asia Minor she is associated with watercourses.

It should not be forgotten that she also has a relationship with physical health, as she was invoked as IGHIéIA and KATHàRSIAS, that is, purifier; during the Panathenaic festivals she was also honored from this point of view.

The name of PARTHèNOS (virgin) is connected to the anecdote of Tiresias who one day, by chance, surprised her bathing. The goddess, not wanting to punish him too cruelly, placed her fingers on his eyes, taking away his ability to see real things, but in exchange granting him the gift of clairvoyance.

Also linked to Athena is the figure of Erichthonius or Erechtheus, a creature half man and half snake, born on earth by Hephaestus and raised by the goddess. Jealously guarded by her in a wicker basket (the daughters of Cecrops who dared to open it deserved death), he was protected by Athena to the point of becoming the first king of Attica and one of the most honored, given that the Erechtheion, the monument on the acropolis of Athens, was dedicated to him.

The ancients therefore attributed to the virgin goddess par excellence this sort of moral maternity which is only apparently contradictory if one considers it as an extension or an accentuation of her strong protective character.

Elisabet Pantazi Cultura dei Greci-Magno Greci-Ελληνων Πολιτισμός

Beautiful “Horoscope” with the 12 Olympian Gods.

Aphrodite is always depicted with her son God “Eros”

It is located in the Louvre museum.

On these aspects of the historic centre of Naples, See C. Negro, “Neapolis. Le ultime scoperte archeologiche”, in “La Rassegna d’Ischia”, 2005, n. 1, pp. 17-24

See “F 9 (Schol. Vatic. in Verg. Georg. 4,563 = F 7 Peter HRR = F 2 Funaioli GRF“ in „Die Communes Historiae des Lutatius: Einleitung, Fragmente, Übersetzung, Kommentar“ von Uwe Walter, Bielefeld, in „Göttinger Forum für Altertumswissenschaft (GFA)“, 12, 2009, , p. 11).

Europe’s First Greek Settlement: Pithekoussai

Celebrated for its thermal springs and verdant landscapes, the volcanic island of Ischia—located in the Bay of Naples—harkens back to the Mycenaean era when it was part of a wide network of Tyrrhenian settlements that traded extensively with the Mycenean Greeks. Although now known for its tourist trade, Ischia—called Pithekoussai during its Greek days—was the first Greek settlement in all of Europe. Enterprising pioneers primarily from the Greek city-state island of Euboea (present-day Evvia) founded the colony in the mid-eighth century BCE naming it Pithekoussai.

B But how did the Greeks arrive at that name? In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder claims that Pithekoussai was named for its numerous pithoi (large terracotta amphoras) which were more common there than in neighboring Iron Age sites. Others insist that the word was derived by the Greek pithekos meaning ape or monkey. Situated on what was then the western-most boundary of the Mediterranean, why was the island named after monkeys? To be sure, there are none nor have there ever been any monkeys in the area. But the notion of monkeys on a combustible island comes from Greek mythology when Zeus transformed naughty forest creatures into monkeys banishing them to a remote volcanic island. Still others surmise that its name may come instead from the Greek word pithekizo which meant “to monkey around” and may have been a term used derisively by mainlanders to refer to the speculative and profiteering Greeks, who originally hailed from the Athens environs, several hundred miles away.

C Hailing from the Euboean cities of Eretria and Chalcis, although Euboeans were the island’s most populous settlers, the Corinthians had a presence in Pithekoussai as well. Yet the Greeks had company on the island. Excavated in the burial sites of the area is a population that is often overlooked when considering colonial settlements—the indigenous people. Based on Italic artifacts found there, speculation had been that the female natives of the community intermarried with the settlers. The theory was that the natives had no say in their culture except by virtue of marriage within the colonial community. But the assumption that the indigenous people were passive and subservient to the colonials has since been debunked. Instead, it has been affirmed that the Italic community were active and vital members working alongside the settlers in Pithekoussai. In fact, extensive trading between the natives and the colonists may have forged their relationship and acted as a chief impetus for setting up the colony in Pithekoussai in the first place.

Indeed, Italic people of the Tyrrhenian region likely lived in the area from the Bronze age onwards, though to date there is no written record of their story. It should be noted that writing was becoming more common around the time the island was being colonized with the Greeks leading the vanguard from the fifth century BCE and beyond. Perhaps, it is because of these inscribed records that we have an historical bias in favor of the influence of the Greeks in the region. That being the case, the Greeks were not Pithekoussai’s only settlers. It is now known there was a sizable establishment of Phoenicians in Pithekossai as well. Indeed, experts believe that the Greek, Phoenician and native communities may not have only worked together on the island but lived together as well, developing a multi-cultural settlement.

D Excavations of burial sites in the area have found the population to be both ethnically and culturally mixed with a populace that was more multi-layered than previously thought sporting a hodgepodge of Italic, Greek and Levantine ethnicities. It is interesting to note, that in the eighth century BCE, the notion of ethnicity was a fluid and evolving concept. Some believe that it was not until around the fifth century BCE that the Greeks began defining themselves vis a vis everyone else. Further, it may have been the colonizing experience in and of itself which advanced their notion of Greek identity with language forging their bound as a Hellenistic people. The word “barbarian” comes from the Greek word “barbaroi,” which meant babbler and was an onomatopoeic term which labeled foreigners as ‘bar-bar’ speakers. Derisive and mocking to those who spoke a language other than some dialect of Greek, the word was relatively uncommon until the fifth century BCE; becoming more and more popular once the Greeks began colonizing and were exposed to a plethora of languages other than their own.

Which begs the question, why on earth would settlers from as far afield as Euboea—a sea-faring island to the east of Athens—or even further afield as Phoenicia—present-day Syria, Lebanon and Northern Israel—be interested in colonizing an island that was on the outer western limit of the Mediterranean? In order to answer this question definitively, it is important to understand what was occurring at the time. Ancient Greece, never known for its arable land, was experiencing a farmland shortage that was becoming pronounced during the population explosion of the Archaic Age. It was because of this scarcity that colonizing other areas from the eighth through the sixth centuries BCE became fashionable to the intrepid ancient Greeks.

E Although the rich fertility of Pithekoussai’s volcanic soil was desirable to the settlers, even more alluring to the Iron Age colonists were its ample iron ore reserves. In the eighth century BCE, iron was the new bronze and the adventurous settlers were willing to travel far and wide for their current metal of choice. Because of its protected, well-positioned harbor along with its vast resources, trade networks were bountiful in Pithekoussai. The island traded heavily not only with their mainland neighbors of Campania, Apulia, Etruria and Latium but also with the Near East and Carthage, amongst others. Throughout Greek settlements, Pithekoussai was recognized as having the widest range of objects from the farthest reaches of the Iron Age Mediterranean.

Today, chief among Pithekoussan objects of interest is a seven-inch cup, originally fired on the island of Rhodes and dated to around 750 BCE. Battered and diminutive, at first glance this artifact is unimpressive, but upon closer inspection an engraving can be found that has sparked no small amount of interest in the academic community. The etching, believed to have been scribbled in Pithekoussai around 725 BCE, is not only the earliest example we have of Greek writing, more compelling still is that this is the first example we have of Greek poetry. Two of the three lines of text are in Homeric hexameter and refer to Nestor, a character from Homer’s Iliad:

“I am Nestor’s cup, good to drink from. Whoever drinks this cup empty, straightaway Desire for beautiful-crowned Aphrodite will seize him.”

F ronically, the earliest recorded evidence we have of Homer’s epic hymn is in the form of a sexual joke. The cup’s humble size is in contrast to Nestor’s cup in the Iliad (11.632-637) which is enormous and too heavy to lift:

“Anyone else would hardly have been able to lift it from the table when it was full, but Nestor could do so quite easily.”

On the one hand, it was a play on words as the cup’s modest size is in direct contrast to Nestor’s cup in the Iliad. On the other hand, it was a bawdy quip as the reference to Aphrodite bespeaks. The fact that Greeks living in the eighth century BCE on the edge of Magna Graecia could jest about the Homeric legends testifies to how deeply ingrained, even prosaic, Homer’s narratives must have been.

G Undeniably, the Iliad was originally composed as an oral hymn, to be sung or recited, possibly as early as 1200 BCE with its written format believed to have been penned anywhere from 725 BCE to 634 BCE. But as a result of this discovery of an etching on this obscure cup in the backwaters of ancient Greece, some scholars now argue that the date of Homer’s poem must be pushed back for knowledge of his verses to be as common as this cup attests. Sadly, in contrast to its amusing engraving this cup has a more sobering epilogue; it was discovered in the grave of a ten-year old boy offered by his father in a funeral pyre. Doubly tragic is that the young lad, who was in death its final recipient, would never know the adult delight the cup’s inscription signified. Alas, the ancients were used to death inching up and making itself comfortable in the unlikeliest of places. The somber conclusion of this cup’s destiny is a reminder that in the Greek world omnipresent death was humor’s dark companion.

Companionable death is the subject for another noteworthy Pithekoussan artifact fashioned at roughly the same time as Nestor’s cup. Considered to be the oldest painted krater in all of Italy, the images on the vase read like a tale from what must have been an all-too common narrative on the seafaring shores of the Mediterranean—a shipwreck. “The Pithekoussai Shipwreck” begins with the image of a capsized ship followed by the figures of sailors in various stages of either swimming or sinking. Of the latter, one sailor—appearing lifeless—is floating on the water. Another sailor’s head is between the jaws of a gargantuan fish. The story’s conclusion ends with a colossal fish standing on its tail demonstrating the enormity of his human feast to one and all.

Could this narrative have also come out of Homer’s epics as some have speculated? As can be expected from a seafaring people there is much about shipwrecks in the Homeric epics. Below are a few key passages which paint a picture close to what is depicted on the krater. One such scene is in the Odyssey after Zeus hurls a thunderbolt at the ship: “All the crew were swept overboard…..,for the god denied them their homecoming” (Odyssey 14.305-13). Then in the Iliad, Achilles mocks Lykaon (one of Priams’s sons).“Now lie there among the fish…your mother will not lay you out on the bier and lament for you…. and fish rising through the swell will dart up under the dark ruffled surface to eat the white fat of Lykaon” (Iliad 21.122-7).

In another scene from the Iliad, Skamandros (the River god of Troy) taunts Achilles:

“I shall wrap his body in sand, and pile an infinite wealth of silt over it, so the Achaeans will not know where they can gather his bones, such is the covering of mud I shall heap on him.” (Iliad 21.316-23).

Because shipwrecks were common in the ancient world, death by sea was a demise most dreaded by the ancient mariners. The horror of not being buried and properly mourned by family on the one hand and becoming a feast for fish on the other is aptly portrayed in both the Pithekoussan shipwreck krater and the ubiquitous Homeric epics demonstrating, once again, death’s hovering presence in the ancient world.

Which brings us to the fate of Pithekoussai. In a booming land of plenty with a population boasting ten thousand at its zenith in 700 BCE, why was this plucky Greek settlement not better known? While it was the rich volcanic soil that initially lured the Greeks and Phoenicians to settle the island of Pithecusae, the reason for its demise may also lie in the soil’s combustible origins. According to geographer and historian Strabo (64 BCE to 24 CE), severe volcanic and earthquake activity impacted Pithekoussai’s acclaim leading one classical scholar to term it “the lid of a cauldron.”

H While geographic activity was harmful to trade, others speculate that political reasons relating to the growth of Cumae on the Italian mainland may have contributed to Pithekoussai’s downfall as well. Nevertheless, an exodus ensued and Pithekoussai’s bustling trade was eventually transferred to neighboring Cumae. Most historians agree that by 500 BCE the settlement of Pithekoussai was all but destroyed by a volcanic eruption of Mount Epomeo, the island’s largest volcano. Perhaps in a fitting Homeric denouement, discovered in a funeral pyre, the fiery fate of Nestor’s cup foreshadowed the incendiary collapse of the once burgeoning land from which its famed inscription had sprung.

Pithekoussai, Ancient Greek Colony of Nestor’s Cup” Celebrated for its thermal springs and verdant landscapes, the volcanic island of Ischia, called Pithekoussai during its ancient Greek days —located in the Bay of Naples—harkens back to the Mycenaean era when it was part of a wide network of Tyrrhenian settlements that traded extensively with the Mycenean Greeks. It was the first Greek colony in all of Europe. Enterprising pioneers primarily from the Greek city-state island of Euboea (present-day Evvia) founded the colony in the mid-eighth century BC naming it Pithekoussai.Zeus’ Monkeys or Pithoi?

But how did the Greeks arrive at that name? In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder claims that Pithekoussai was named for its numerous pithoi (large terracotta amphoras) which were more common there than in neighboring Iron Age sites. Others insist that the word was derived by the Greek pithekos meaning ape or monkey. Situated on what was then the western-most boundary of the Mediterranean, why was the island named after monkeys? To be sure, there are none nor have there ever been any monkeys in the area. But the notion of monkeys on a combustible island comes from Greek mythology when Zeus transformed naughty forest creatures into monkeys banishing them to a remote volcanic island. Still others surmise that its name may come instead from the Greek word pithekizo which meant ‘to monkey around’ and may have been a term used derisively by mainlanders to refer to the speculative and profiteering Greeks, who originally hailed from the Athens environs, several hundred miles away.

Hailing from the Euboean cities of Eretria and Chalcis, although Euboeans were the island’s most populous settlers, the Corinthians had a presence in Pithekoussai as well. Yet the Greeks had company on the island. Excavated in the burial sites of the area is a population that is often overlooked when considering colonial settlements—the indigenous people. Based on Italic artifacts found there, speculation had been that the female natives of the community intermarried with the settlers. The theory was that the natives had no say in their culture except by virtue of marriage within the colonial community. But the assumption that the indigenous people were passive and subservient to the colonials has since been debunked. Instead, it has been affirmed that the Italic community were active and vital members working alongside the settlers in Pithekoussai. In fact, extensive trading between the natives and the colonists may have forged their relationship and acted as a chief impetus for setting up the colony in Pithekoussai in the first place.

Indeed, Italic people of the Tyrrhenian region likely lived in the area from the Bronze age onwards, though to date there is no written record of their story. It should be noted that writing was becoming more common around the time the island was being colonized with the Greeks leading the vanguard from the fifth century BCE and beyond. Perhaps, it is because of these inscribed records that we have an historical bias in favor of the influence of the Greeks in the region. That being the case, the Greeks were not Pithekoussai’s only settlers. Indeed, experts believe that the Greek and the later Semitic Phoenician and native communities may not have only worked together on the island but lived together as well, developing a multi-cultural settlement.

Excavations of burial sites in the area have found the population to be both ethnically and culturally mixed with a populace that was more multi-layered than previously thought sporting a hodgepodge of Italic, Greek and Levantine ethnicities. It is interesting to note, that in the eighth century BCE, the notion of ethnicity was a fluid and evolving concept. Some believe that it was not until around the fifth century BCE that the Greeks began defining themselves vis a vis everyone else. Further, it may have been the colonizing experience in and of itself which advanced their notion of Greek identity with language. The word “barbarian” comes from the Greek word “barbaroi,” which meant babbler and was an onomatopoeic term which labeled foreigners as ‘bar-bar’ speakers. Derisive and mocking to those who spoke a language other than some dialect of Greek, the word was relatively uncommon until the fifth century BCE; becoming more and more popular once the Greeks began colonizing and were exposed to a plethora of languages other than their own.

Which begs the question, why on earth would settlers from as far afield as Euboea—a sea-faring island to the east of Athens—of the Archaic Age. It was by colonizing other areas from the 5000 BC(Cretans) through the sixth centuries BCE became fashionable to the intrepid ancient Greeks.

Undeniably, the Iliad was originally composed as an oral hymn, to be sung or recited, possibly as early as 1200 BCE with its written format believed to have been penned anywhere from 725 BCE to 634 BCE. But as a result of this discovery of an etching on this obscure cup in the backwaters of ancient Greece, some scholars now argue that the date of Homer’s poem must be pushed back for knowledge of his verses to be as common as this cup attests. Sadly, in contrast to its amusing engraving this cup has a more sobering epilogue; it was discovered in the grave of a ten-year old boy offered by his father in a funeral pyre. Doubly tragic is that the young lad, who was in death its final recipient, would never know the adult delight the cup’s inscription signified. Alas, the ancients were used to death inching up and making itself comfortable in the unlikeliest of places. The somber conclusion of this cup’s destiny is a reminder that in the Greek world omnipresent death was humor’s dark companion.

Companionable death is the subject for another noteworthy Pithekoussan artifact fashioned at roughly the same time as Nestor’s cup. Considered to be the oldest painted krater in all of Italy, the images on the vase read like a tale from what must have been an all-too common narrative on the seafaring shores of the Mediterranean—a shipwreck. “The Pithekoussai Shipwreck” begins with the image of a capsized ship followed by the figures of sailors in various stages of either swimming or sinking. Of the latter, one sailor—appearing lifeless—is floating on the water. Another sailor’s head is between the jaws of a gargantuan fish. The story’s conclusion ends with a colossal fish standing on its tail demonstrating the enormity of his human feast to one and all.

Could this narrative have also come out of Homer’s epics as some have speculated? As can be expected from a seafaring people there is much about shipwrecks in the Homeric epics. Below are a few key passages which paint a picture close to what is depicted on the krater. One such scene is in the Odyssey after Zeus hurls a thunderbolt at the ship: “All the crew were swept overboard…..,for the god denied them their homecoming” (Odyssey 14.305-13). Then in the Iliad, Achilles mocks Lykaon (one of Priams’s sons).“Now lie there among the fish…your mother will not lay you out on the bier and lament for you…. and fish rising through the swell will dart up under the dark ruffled surface to eat the white fat of Lykaon” (Iliad 21.122-7).

In another scene from the Iliad, Skamandros (the River god of Troy) taunts Achilles:

“I shall wrap his body in sand, and pile an infinite wealth of silt over it, so the Achaeans will not know where they can gather his bones, such is the covering of mud I shall heap on him.” (Iliad 21.316-23).

Because shipwrecks were common in the ancient world, death by sea was a demise most dreaded by the ancient mariners. The horror of not being buried and properly mourned by family on the one hand and becoming a feast for fish on the other is aptly portrayed in both the Pithekoussan shipwreck krater and the ubiquitous Homeric epics demonstrating, once again, death’s hovering presence in the ancient world.

Which brings us to the fate of Pithekoussai. In a booming land of plenty with a population boasting ten thousand at its zenith in 700 BCE, why was this plucky Greek settlement not better known? While it was the rich volcanic soil that initially lured the Greeks and Hellenic Phoenicians to settle the island of Pithecusae, the reason for its demise may also lie in the soil’s combustible origins. According to geographer and historian Strabo (64 BCE to 24 CE), severe volcanic and earthquake activity impacted Pithekoussai’s acclaim leading one classical scholar to term it “the lid of a cauldron.”

While geographic activity was harmful to trade, others speculate that political reasons relating to the growth of Cumae on the Italian mainland may have contributed to Pithekoussai’s downfall as well. Nevertheless, an exodus ensued and Pithekoussai’s bustling trade was eventually transferred to neighboring Cumae. Most historians agree that by 500 BCE the settlement of Pithekoussai was all but destroyed by a volcanic eruption of Mount Epomeo, the island’s largest volcano. Perhaps in a fitting Homeric denouement, discovered in a funeral pyre, the fiery fate of Nestor’s cup foreshadowed the incendiary collapse of the once burgeoning land from which its famed inscription had sprung.

Pithekoussai, Ancient Greek Colony of Nestor’s Cup” Celebrated for its thermal springs and verdant landscapes, the volcanic island of Ischia, called Pithekoussai during its ancient Greek days —located in the Bay of Naples—harkens back to the Mycenaean era when it was part of a wide network of Tyrrhenian settlements that traded extensively with the Mycenean Greeks. It was the first Greek colony in all of Europe. Enterprising pioneers primarily from the Greek city-state island of Euboea (present-day Evvia) founded the colony in the mid-eighth century BC naming it Pithekoussai.Zeus’ Monkeys or Pithoi?

But how did the Greeks arrive at that name? In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder claims that Pithekoussai was named for its numerous pithoi (large terracotta amphoras) which were more common there than in neighboring Iron Age sites. Others insist that the word was derived by the Greek pithekos meaning ape or monkey. Situated on what was then the western-most boundary of the Mediterranean, why was the island named after monkeys? To be sure, there are none nor have there ever been any monkeys in the area. But the notion of monkeys on a combustible island comes from Greek mythology when Zeus transformed naughty forest creatures into monkeys banishing them to a remote volcanic island. Still others surmise that its name may come instead from the Greek word pithekizo which meant ‘to monkey around’ and may have been a term used derisively by mainlanders to refer to the speculative and profiteering Greeks, who originally hailed from the Athens environs, several hundred miles away.

The Pithecusan Shipwreck: this new drawing is taken from a Late Geometric crater made on Ischia—the first figured Geometric vase found in Italy.